Exercise - R basics

In this exercise you will practice:

- to set up your working environment (project) in RStudio

- to write R scripts and execute code

- to access data in dataframes (the most important data class in R)

- to query (filter) dataframes

- to spot typical mistakes in R code

Please carefully follow the instructions for setting up your working environment and ask other participants

Tasks:

- Read the text below

- Run the examples

- Do the specific R exercises that are in the following pink block:

What is the answer to everything?

Hints:

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

Setting up the working environment in RStudio

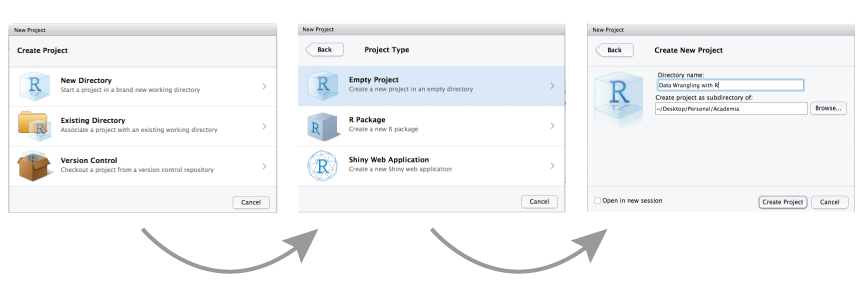

Your first task is to open RStudio and create a new project for the course.

- Click the ‘File’ button in the menu, then ‘New Project’ (or the second icon in the bar below the menu “Create a project”).

- Click “New Directory”.

- Click “New Project”.

- Type in the name of the directory to store your project, e.g. “IntroStatsR”.

- “Browse” to the folder on your computer where you want to have your project created.

- Click the “Create Project” button.

For all exercises during this week, use this project! You can open it via the file system as follows (please try this out now):

- (Exit RStudio).

- Navigate to the directory where you created your project.

- Double click on the “IntroStatsR.Rproj” file in that directory.

You should now be back to RStudio in your project.

In the directory of the R project, generate a folder “scripts” and a folder “data”. You can do this either in the file directory or in RStudio. For the latter:

- Go to the “Files” panel in R Studio (bottom right panel).

- Click the icon “New Folder” in the upper left corner.

- Enter the folder name.

- The new folder is now visible in your project directory.

The idea is that you will create an R script for each exercise and save all these files in the scripts folder. You can do this as follows:

- Click the “File” button in the menu, then “New File” and “R Script” (or the first icon in the bar below the menu and then “R Script” in the dropdown menu).

- Click the “File” button in the menu, then “Save” (or the “Save” icon in the menu).

- Navigate to your scripts folder.

- Enter the file name, e.g. “Exercise_01.R”.

- Save the file.

A few hints before you can start

Remember the different ways of running code:

- click the “Run” button in the top right corner of the top left panel (code editor) OR

- hit “Ctrl”+“Enter” (MAC: “Cmd”+“Return”)

RStudio will then run

- the code that is currently marked OR

- the line of code where the text cursor currently is (simply click into that line)

If you face any problems with executing the code, check the following:

- all brackets closed?

- capital letters instead of small letters?

- comma is missing?

- if RStudio shows red attention signs (next to the code line number), take it seriously

- do you see a “+” (instead of a “>”) in the console? stop executions with “esc” key and then try again.

Have a look at the shortcuts by clicking “Tools” and than “Keybord Shortcuts Help”!!

Basic data structures in R

Before we work with real data, we should first recap important data structures in R

A single value (type does not matter) is called a scalar (it is just one value):

a = 5

print(a)

## [1] 5

this_letter = "A"

print(this_letter)

## [1] "A"<- and = are assignment operators, they are equivalent and are used to assign values, data, or objects to a variable.

In R you can use any type of name for a variable, you can even mix numbers and dots in the name: test5 or test.5, but there is one restriction, no special symbols (as they are usually operators or functions) and a name cannot start with a number, for example 5test will throw an error.

However, usually we want to assign several values to a variable. For example, a dataset consists of several columns (=variables). We can use the function c(...) to connect (or concatenate) several values:

age = c(20, 50, 30, 70)

print(age)

## [1] 20 50 30 70

names = c("Anna", "Daniel", "Martin", "Laura")

print(names)

## [1] "Anna" "Daniel" "Martin" "Laura"Vectors

You can only concatenate values from the same data type! If they are different, all will be casted to the same data type!

print(c("Age", 5, TRUE))

## [1] "Age" "5" "TRUE"The c(...) function returns a vector which is a one-dimensional array. You can access elements of the vector by using the square brackets [which_element]:

age[2] # second element

## [1] 50

age[1] # first element

## [1] 20This is known as indexing. And there are a few tricks:

Use

[-n]to return all elements except forn:age[-2] # return all except for the second element ## [1] 20 30 70Use another vector to return several elements at once:

age[c(1, 3)] # return first and third elements ## [1] 20 30 age[-c(1,3)] # return all elements except for first and third elements ## [1] 50 70Use

<-or=to re-assign/change elements in your vectorage[2] = 99 print(age) ## [1] 20 99 30 70

The : operator in R is not the division operator. It actually creates a range of integer values with start:end:

1:5

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5Which is really useful for indexing:

age[1:3]

## [1] 20 99 30Matrix

Usually a dataset consist not of only one variable/vector but of several variables (columns) and observations (rows), for example:

age = c(20, 30, 32, 40)

weight = c(60, 70, 72, 80)we can use higher order data structures to combine these variables in a two dimensional array (like we would, for example, do in excel) using the matrix(...) function:

dataset = matrix(NA, 4, 2)

dataset # empty dataset

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] NA NA

## [2,] NA NA

## [3,] NA NA

## [4,] NA NA

dataset[,1] = age

dataset[,2] = weight

dataset

## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 20 60

## [2,] 30 70

## [3,] 32 72

## [4,] 40 80Similar to a vector we can index certain elements in the matrix or at the same time entire rows or columns. Since is has now two dimensions, we change [i] to [row_i, col_j]. The first argument specifies which row and the second argument which column should be returned. There are again a few handy tricks, above we left the rows empty (dataset[,1]) which will R interpret as “use all rows”, in that way we can print/return entire columns or rows:

dataset[,1] # first column

## [1] 20 30 32 40

dataset[1,] # first row

## [1] 20 60Don’t worry, you don’t have to create your own data sets like we did in this section. When you import your data into R, it is automatically returned as a matrix (or as data.frame, see below).

A limitation of the matrix() is that is can only consist of one data type (like the vectors), if we mix the data types, all will be cast to the same data type:

cbind(age, names)

## age names

## [1,] "20" "Anna"

## [2,] "30" "Daniel"

## [3,] "32" "Martin"

## [4,] "40" "Laura"cbind() is a function that combines columns (“column binds”), it can be used as a shortcut to create a matrix from several vectors. Another important command is rbind(...) which combines vectors (or matrices) over their rows:

rbind(age, names)

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## age "20" "30" "32" "40"

## names "Anna" "Daniel" "Martin" "Laura"Data.frames

The data.frame() can handle variables with different data types. Data.frames are similar to matrices, they are two dimensional and the indexing is the same:

df = data.frame(age, names, weight)

df

## age names weight

## 1 20 Anna 60

## 2 30 Daniel 70

## 3 32 Martin 72

## 4 40 Laura 80

str(df)

## 'data.frame': 4 obs. of 3 variables:

## $ age : num 20 30 32 40

## $ names : chr "Anna" "Daniel" "Martin" "Laura"

## $ weight: num 60 70 72 80(we will talk below more about data.frames)

Getting an overview of a dataset

We work with the airquality dataset:

dat = airqualitySeveral example datasets are already available in R. The airquality dataset with daily air quality measurements (see ?airquality). Another famous dataset is the iris dataset with flower trait measurements for three species (see ?iris).

Copy the code into your code editor and execute it.

Before working with a dataset, you should always get an overview of it. Helpful functions for this are:

str()View()head()andtail()

Try out these functions and provide answers to the following questions:

- What is the most common atomic class in the airquality dataset?

- How many rows does the dataset have?

- What is the last value in the column “Temp”?

To see all this, run

dat = airquality

View(dat)

str(dat)

head(dat)

tail(dat)Hints:

- Run

str(airquality) - See

?nrowor?dim - Run

tail(airquality$Temp)

What is the most common atomic class in the airquality dataset?

- integer

- function

str()helps to find this out

How many rows does the dataset have?

- 153

- this is easiest to see when using the function

str(dat) dim(dat)ornrow(dat)give the same information

What is the last value in the column “Temp”?

- 68

tail(dat)helps to find this out very fast

Accessing rows and columns of a data frame

You have seen how you can use squared brackets [ ] and the dollar sign $ to extract parts of your data. Some people find this confusing, so let’s repeat the basic concepts:

- squared brackets are used as follows:

data[rowNumber, columnNumber] - the dollar sign helps to extract colums with their name (good for readability):

data$columnName - this syntax can also be used to assign new columns, simply use a new column name and the assign operator:

data$newColName <-)

The following lines of code assess parts of the data frame. Try out what they do and sort the code lines and their meaning:

Which of the following commands

dat[2, ]

dat[, 2]

dat[, 1]

dat$Ozone

new = dat[, 3] + dat[, 4]

dat$new = dat[, 3] + dat[, 4]

dat$NAs = NA

NA -> dat$NAs will get you

- get the second row

- get column Ozone

- generate a new column with NA’s

- calculate the sum of columns 3 and 4 and assign to a new column

Hint: Some of the code lines actually do the same; chose the preferred way in these cases.

Filtering data

To use the data, you must also be able to filter it. For example, we may be interested in hot days in July and August only. Hot days are typically defined as days with a temperature equal or > 30°C (or 86°F as in the dataset here). Imagine, your colleague tried to query the data accordingly. She/he also found a mistake in each of the first 4 rows and wants to exclude these, but she/he is very new to R and made a few common errors in the following code:

# Return only rows where the temperature is exactly is 86

dat[dat$Temp = 86, ]

# Return only rows where the temperature is equal or larger than 86

dat[dat$Temp >= 86]

# Exclude rows 1 through 4

dat[-1:4, ]

# Return only rows for the months 7 or 8

dat[dat$Month == 7 | 8, ]Can you fix his/her mistakes? These hints may help you:

- rows or columns can be excluded, if the numbers are given as negative numbers

==means “equals”&means “AND”|means “OR” (press “AltGr”+“<” to produce |, or “option”+“7” on MacOS)- executing the erroneous code may help you to spot the problem

- run parts of the code if you don’t understand what the code does

- the last question is a bit trickier, no problem if you don’t find a solution

The %in% operator is useful when you want to check whether a value is inside a vector or not:

5 %in% c(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

## [1] TRUEWe will discuss the results together.

When you are finished, save your R script!

Last task - Install EcoData package

During the course, we will use some datasets that we compiled in the \(EcoData\) package. To access the datasets, you need to install the package from github. To do this, you will also need to install the \(devtools\) package.

Try the following code to install the two packages:

install.packages("devtools")

library(devtools)

devtools::install_github(repo = "TheoreticalEcology/EcoData",

dependencies = F, build_vignettes = F)

library(EcoData)Remember that you have to install a package only once. If you open R Studio the next time, it is enough to run library(EcoData).

Alternative ways to get EcoData

If the installation didn’t work, download the package file manually from

https://github.com/TheoreticalEcology/ecodata/releases/download/v0.2.1/EcoData_0.2.1.tar.gz

Store the file on your computer in the same folder where you created your R project. Then run the following code:

install.packages("EcoData_0.2.1.tar.gz",

repos = NULL, type = "source")

library(EcoData)If this wasn’t successful either, you can download the combined datasets from elearning (see Organisation and every-day material)

Store the file on your computer in the same folder where you created your R project. Then run the following code:

load("EcoData.Rdata")(Note that you will not be able to access the dataset descriptions when you use this option).

Bonus - Advanced programming

Until now we have only learned how to use functions and indexing of data structures. But what are functions?

Functions

A functions are self contained blocks of code that do something, for example, the average of a vector is given by:

\[ Average = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N x_i \]

In R we can easily calculate the sum over a vector by using the function sum():

values = 1:10

print(values)

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

# Average

sum(values)/length(values)

## [1] 5.5To do that now more easily and in a comprehensive way for many different variables, we can define a function to calculate the mean:

average = function(x) {

average = sum(x)/length(x)

return(average)

}

average(values)

## [1] 5.5A function consists of: - An expressive name - Arguments function(arg1, arg2, arg3), the arguments can be used to pass the data to the function, or to change the behaviour of the function (see below) - A function body, inside curly brackets { } where the actual magic happens - return(...) what should be returned from the function

The advantages: - you can compress big code blocks within one function call - reproducibility, we avoid writing the same code again and again, if we want to change the way how we calculate the average, we have to change it only in one place - clarity, the name of the function can give us a hint about what the function is doing

Arguments

Arguments can be either used to pass data to the function or to change the behaviour of the function. Moreover, you can set default values to the function. If arguments have default values, they do not have to be specified (specifiying means that we have to fill this argument):

# Should NAs be removed or not

average = function(x, remove_na) {

if(!remove_na) {

average = sum(x)/length(x)

} else {

average = sum(x, na.rm = TRUE)/length(x[complete.cases(x)])

}

return(average)

}

values = c(5, 4, 3, NA, 5, 2)

# no default option for remove_na, we have to specify it!

average(values, remove_na = TRUE)

## [1] 3.8

# In this case, it is better to set a default option for remova_na:

average = function(x, remove_na = TRUE) {

if(!remove_na) {

average = sum(x)/length(x)

} else {

average = sum(x, na.rm = TRUE)/length(x[complete.cases(x)])

}

return(average)

}

average(values)

## [1] 3.8if(condition) { } else { } the if/else statements runs code if a certain condition is true or not. If the condition is true, the first code block { } is run, if it is false, the second (after the else) is run:

values = 1:5

if(length(values) == 5) {

print("This vector has length 5")

} else {

print("This vector has not length 5")

}

## [1] "This vector has length 5"Arguments are matched by the name or, if names are not specified, by the order:

func(x1, x2, x3) will be interpreted as func(arg1 = x1, arg2 = x2, arg3 = x3)

But be careful, if you are unsure about the correct order, you should pass them by their name (func(arg1 = x1, arg2 = x2, arg3 = x3))

Loops

Loops are another important code structure. Example: We want to go over all values of a vector, calculate the square root of it, and overwrite the old value with the new value:

values = c(20, 33, 25, 16)

values[1] = sqrt(values[1])

values[2] = sqrt(values[2])

values[3] = sqrt(values[3])

values[4] = sqrt(values[4])Now what should we do if we have thousands of observations? Loops are the solution! We can use them to automatically “run” a specific vector and then do something with it (well it sounds cryptic but it is actually quite easy):

for(i in 1:4) { # i in 1:4 means that i should be 1, 2, 3, and 4

print(i)

}

## [1] 1

## [1] 2

## [1] 3

## [1] 4

# Let's use it to automatize the previous computation:

for(i in 1:4) {

values[i] = sqrt(values[i])

}

values

## [1] 2.114743 2.396782 2.236068 2.000000

# Even better: do not hardcode the length of the vector:

for(i in 1:length(values)) {

values[i] = sqrt(values[i])

}

values

## [1] 1.454215 1.548154 1.495349 1.414214Our code will now always work, even if we change the length of the values variable!

Write functions for:

Calculate the sum for all values in a matrix given by (we want to write our own implementation of the internal

sum(...)function):my_matrix = matrix(1:200, 20, 10)Use the internal

sum(...)function to check whether your function is correct!Extend the function with arguments that specify that the sum should be calculate over rows, columns, or both (if we calculate the sum over rows or columns, then a vector with n sums for n rows or n columns should be returned).